Peeling Back the Layers

Frescos and flying creatures

From 1957 to 1966, Florence hosted a series of unique exhibitions high above the city at the Forte Belvedere. Crowds gathered and jostled to get up close and personal with massive frescos that had been detached from the wall in a process called the strappo (the literal translation is ‘rip’). This consists of an incision being made around the fresco then applying a canvas coated with water-soluble glue to the pictorial surface which is then pulled off when dry so that the paint film comes off. The paint film layer is then applied to a canvas and voilà, you have a detached fresco.

As you can imagine, the process is extremely risky but it does allow for the preservation of frescos that are in danger of ruin. From an educational perspective, the technique of the strappo meant that our knowledge about frescos increased exponentially in the 1950s and 60s.

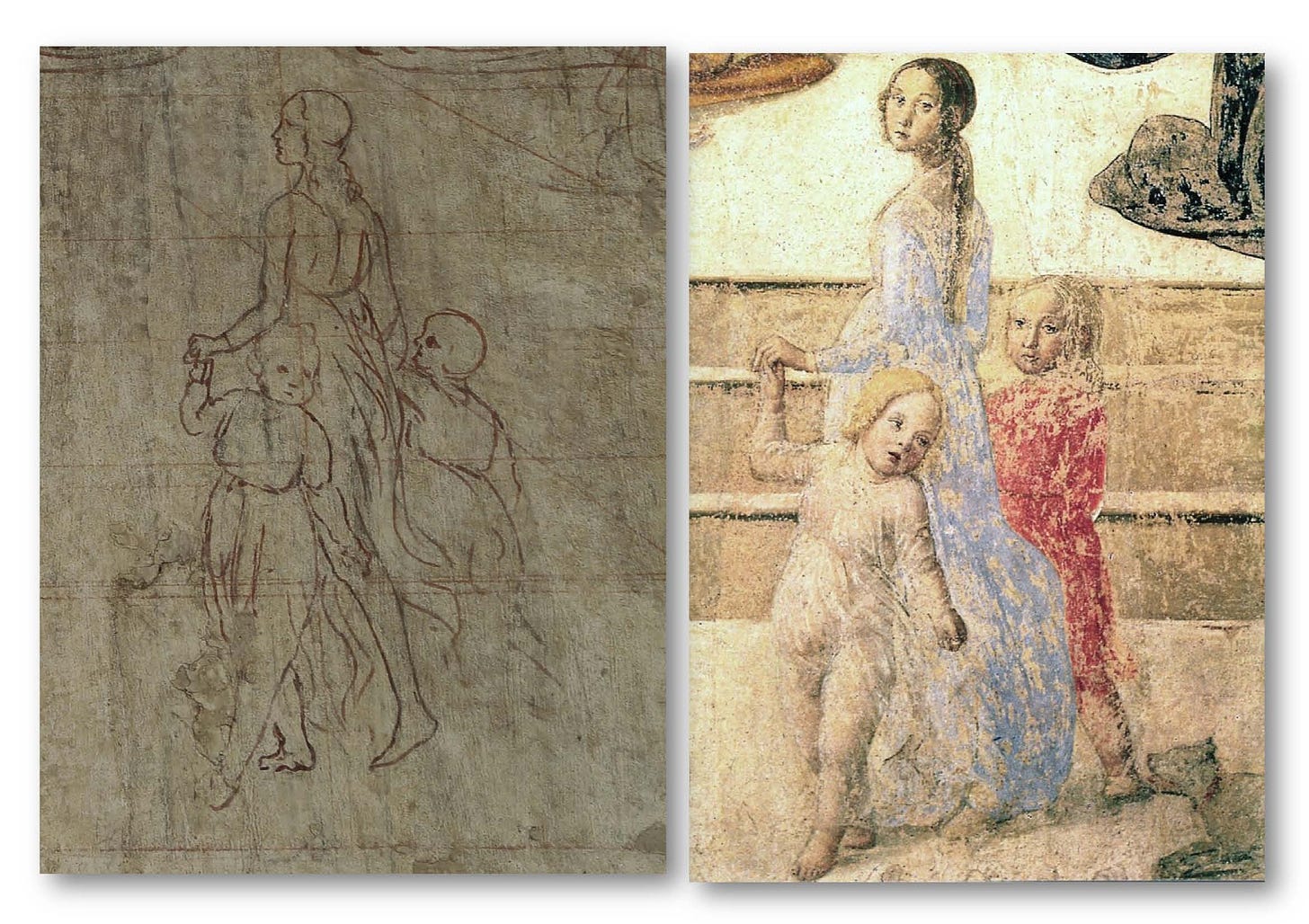

The exhibitions at the Forte Belvedere didn’t just display the pictorial layer of the frescos, however; the sinopias, the brush underdrawings of frescos made of red ochre dissolved in water, were also mounted and shown for all to see. As underdrawings, sinopias are sketches that an artist would have rapidly dashed off to indicate the positions of the objects to be painted on the layer of intonaco.

They range from more to less detailed, but in every case sinopias are private, meant to be seen only by the artist and his team—they never would have anticipated the paint film being pulled back to expose their private and temporary visual thoughts. They certainly would not have understood our fascination with sinopias, but we know that they speak directly to our desire to be privy to the spontaneous act of creation.

Years ago, a very curious client who peppered me with non-stop, ranging questions said that doing a tour with me was like being able to jump inside and roam around my brain for three hours. I loved that. When a curious viewer sees a sinopia they get access to a hidden part of the process of a Renaissance master, they get to roam around in their brain for a bit. What a dream.

Sinopias are the technical side of the fresco, though, and while they do reveal some of the immediacy and creative spark, they are not the whole story. Because we never get the whole story behind the creation of a Renaissance fresco, we get to make it up. As a result, one of my favorite past-times is reading imagined backstories of Renaissance art.

I love that Ali Smith came across an image of a fresco in Ferrara featured in Frieze magazine while on vacation and then followed her curiosity and instincts to craft the novel How to Be Both, a story that revolves in part around the artist Francesco del Cossa.

In a delicious case of multi-layered ekphrasis, Maggie O’Farrell read a poem by Robert Browning that then led her to an oil painting that led her to pen her novel The Marriage Portrait, which imagines the story behind the painting and the life of Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici and her horrible husband, Alfonso d’Este

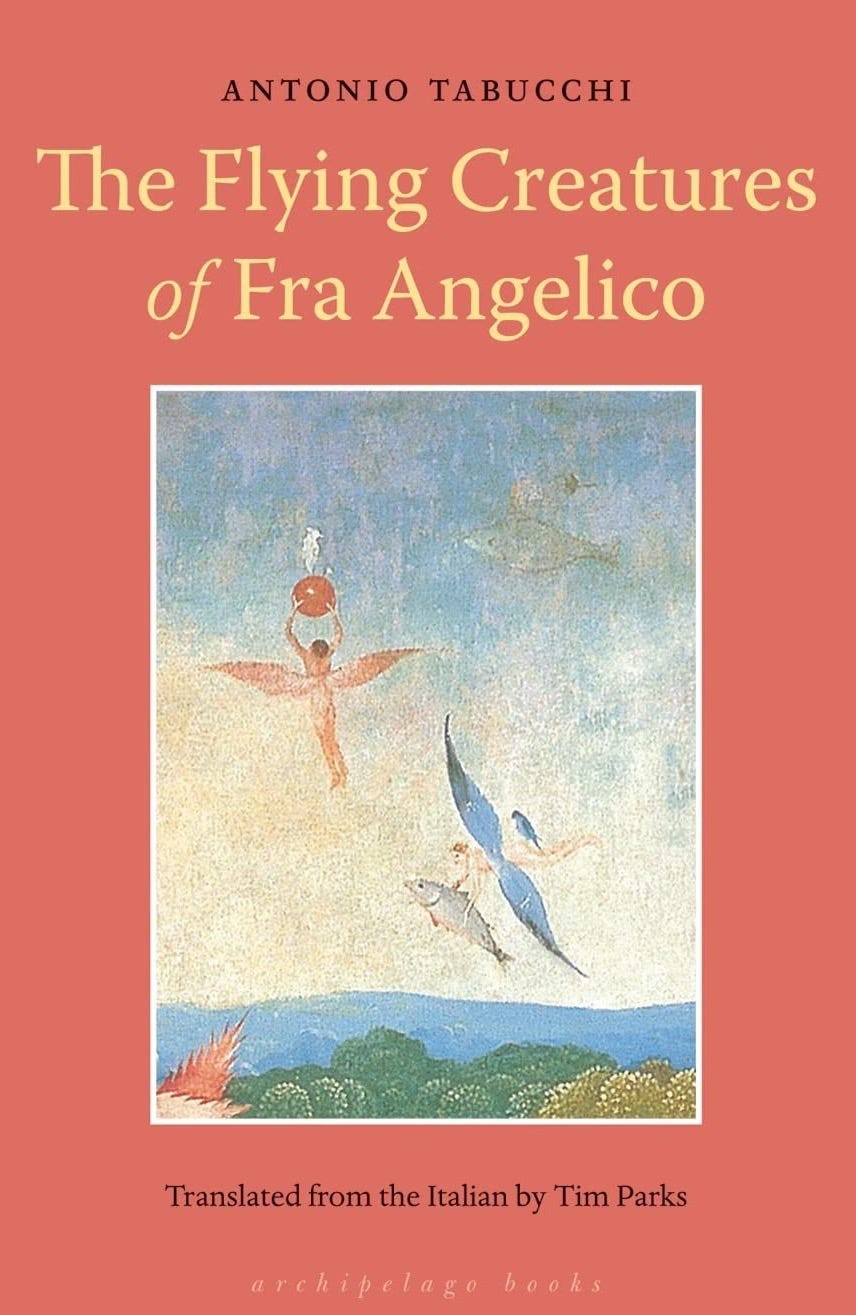

In terms of narrative, however, one little story by Antonio Tabucchi has captured me lately and refused to let me go. It is the ultimate creative imagining of what is going on a Renaissance artist’s brain—reading it made me feel like I can wiggle into these frescos and dream a little.

Titled The Flying Creatures of Fra Angelico, it is the tale of Fra Giovanni of Fiesole (we know him as Fra Angelico) who, while tending to the vegetable garden at the convent of San Marco, receives a visit from three different flying creatures. As usual with Tabucchi’s writing, it is a story whose surreal elements are balanced by a grounded realism, often quite literally as Fra Giovanni tries to explain the soil and the earth to these creatures who have come to our planet from another dimension.

The first creature arrives ‘on a Thursday towards the end of June’ careening into a pear tree and getting stuck. It is soft and pink, with arms like a plucked chicken, turkey-like feet, the face of an aged baby, and sporting a pair of massive wings:

From the creature’s shoulder blades, like incredible triangular sails, rose two enormous wings which covered the entire foliage of the tree and which moved in the breeze together with the leaves. They were made of different coloured feathers, ochre, yellow, deep blue, and an enormous emerald green the colour of a kingfisher, and every now and then they opened like a fan, almost touching the ground, then closed again, in a flash, disappearing behind each other.

The creature communicates through code by wiggling certain feathers:

‘Why do I understand what you say?’ The creature opened his arms as far as his position allowed, as if to say, I haven't the faintest idea. So that Fra Giovanni concluded: ‘Obviously I understand you because I understand you.’

Fra Giovanni then helps the creature down from the tree and goes about explaining the earth to it, the soil, the clumps of dirt, the vegetables and so on. The friar approaches his superior and explains that the creature cannot be inside because it doesn’t know what geometry is—it can’t conceive of space if it is enclosed. Even though the prior cannot see the creature, he recognizes it as a pilgrim that has lost its way and to whom hospitality must be offered.

And at dawn the next morning, two other creatures arrive:

One hovered in the air like a dragonfly, then landed with legs wide apart on the wall. He sat there a moment, astride the wall, as if undecided whether to fall down on this side or that, until at last he crashed down headfirst into the rosemary bushes in the flower bed. The second creature meanwhile turned in two spiralling loops, an acrobat’s pirouette almost, like a strange ball, because he was a roly-poly sort of being without a lower part to his body, just a chubby bust that ended in a greenish brushlike tall with thick, abundant plumage that must serve both as driving force and rudder. And like a ball he came down amongst the rows of lettuce, bouncing two or three times, so that what with his shape and greenish colour you would have thought he was a head of lettuce a bit bigger than the others off larking about thanks to some trick of nature.

The dragonfly creature is decidedly feminine, light and airy and blonde, with the face of one of Fra Giovanni’s neighbors from his village, a young and beautiful girl called Nerina, who had tempted him in adolescence. The roly-poly is more of a loop, a bust terminating in a long tail. Fra Giovanni takes the two creatures over and puts them with the other one and they all rejoice at being reunited.

That night, the dragonfly, seductively reminiscent of Nerina once again, visits Fra Giovanni’s cell.

There was a full moon, and bright moonlight projected the square of the window onto the brick floor. Fra Giovanni caught an intense odour of basil, so strong it gave him a sort of heady feeling.

Tomorrow you must paint us, that's why we came.

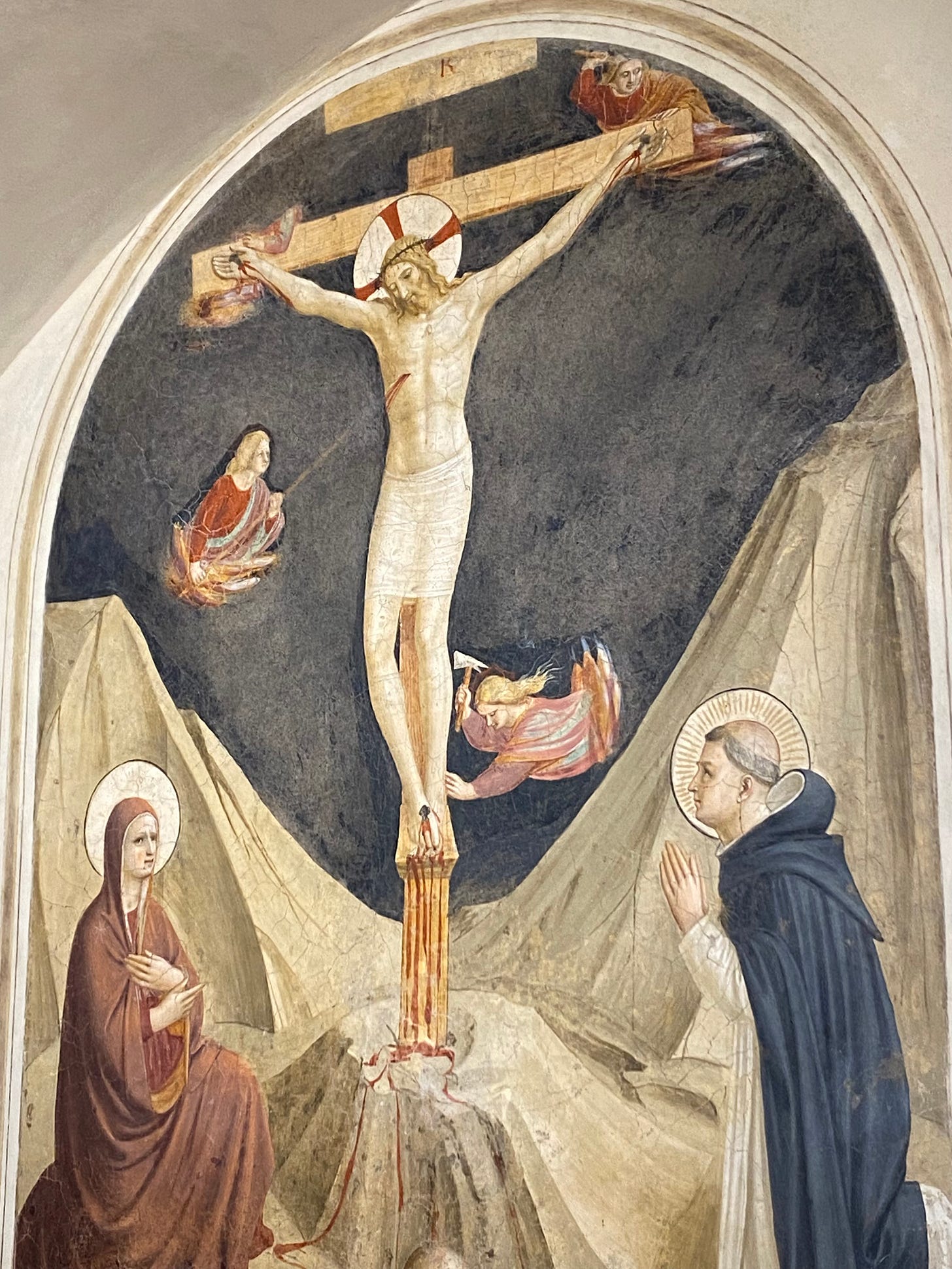

The friar wakes at dawn, says his prayers and then goes out to the cage to choose the first model. He then goes into Cell 23, where he had painted a Crucifixion some days before.

He had asked his helpers to paint the background verdaccio, a mixture of ochre, black and vermilion, since he wanted this to be the colour of Mary's desperation as she points, petrified, at her crucified son.

But now Fra Giovanni wants to include this little flying creature to lighten the Virgin’s grief, so he sets out painting some ‘divine beings’ who hammer the nails into Christ’s hands and feet. He brings the creature into the cell and lays it down on a stool on its stomach so it looked like it was taking flight and begins to paint.

Fra Giovanni then goes into Cell 34 to add a figure to another previously completed fresco, this time an Agony in the Garden.

The painting looked finished, as if there were no more space to fill; but he found a little corner above the trees to the right and there he painted the dragonfly with Nerina’s face and the translucent golden wings. And in her hand he placed a chalice, so that she could offer it to Christ.

Last, he paints the bird-like creature who had arrived first—the one with the enormous rainbow wings. In need of a large space, he chooses the wall in the first corridor and begins.

First he painted a portico, with Corinthian columns and capitals, and then a glimpse of a garden ending in a palisade. Finally he arranged the creature in a genuflecting pose, leaning him against a bench to prevent him from falling over; he had him cross his hands on his breast in a gesture of reverence and said to him: ‘I’ll cover you with a pink tunic, because your body is too ugly. I’ll draw the Virgin tomorrow. You hang on this afternoon and then you can all go. I’m doing an Annunciation.’

Fra Giovanni finishes the painting that evening and then feels tired and melancholy because there was nothing left to do and the moment had passed.

He went to the cage and found it empty. Just four or five feathers had got caught in the net and were twitching in the fresh wind coming down from the Fiesole hills. Fra Giovanni thought he could smell an intense odour of basil, but there was no basil in the garden.

While I am infinitely grateful to the restorers for developing the technique of the strappo, to me nothing compares to our ability to imagine what was going through the minds of these artists as they created. Here’s to giving a backstory to all the ‘flying creatures’ of Renaissance art.

✨🌟💫 Register for Heaven Bound: The Life and Art of Fra Angelico✨🌟💫

This is a lovely tale and makes me like Fra Angelico a lot!

George Macdonald created ugly creatures of fantasy but great character in “The Princess and Curdie”

I wonder if he knew of Fra Angelico and his creatures?

Problem solved via Eventbrite!💪🏽